Blog

Topics

- Years Have Past

- Another victim comes forward...

- How the pandemic is affecting mental health – and what you can do about it

- What happened to #MeToo in the 2020 election?

- Depression

- Healing Through History

- I Just Want Him to Get It.

- Can You Hear Them Now? Good.

- Releasing the Past: Unburdening the Present

- Intro- Thanks for Asking: A Blog by Hope Harbor

Years Have Past

By Jill M.

September 22, 2021

Years have past

Pages of my life written

My face has changed

My family grown

That little girl inside my head

Has shown her face

Come out from the dark

Taken off that mysterious mask

Shared her story

Bared her soul

That little girl doesn’t have to hide anymore

The shame and guilt has lifted

I haven’t done anything wrong

No more secrets and lies

That little girl doesn’t appear frightened so much anymore

That little girl has told me it’s ok

She can be apart of my memories

Not trapped anymore

She has taken my hand and said I can let go

I can see a future free of him

And those that let him be

Recognize my differences and celebrate them

I was allowed to share my story

Never was I judged

I trusted

I was shown that I’m ok

Shown I can live without shame and contempt

I feel free because I have been shown

That I’m ok I’m not weird

You have helped free me from my internal prison

Let me see I’m worthwhile

It’s never to late

From the bottom of my heart

And from that little girl

You have given me the hope I so desperately needed

Taken me on a journey deep and buried

A journey I was so ready for

Years of silence and pain

You have helped set me free

Another victim comes forward...

By Alayna Milby

March 2, 2021

Over the past week, the news circulation has included headlines about women telling their experiences of being sexually harassed by NY governor, Andrew Cuomo. I wanted to take this opportunity to share why we see more survivors come forward after the first one. It can feel like the flood gates have been opened.

Years ago, maybe before I started working at Hope Harbor, I was in a Waffle House. There was a man sitting at the bar staring at me with what I can only explain as a creepy smile. He stared at me for an amount of time that is unquestionable as to how uncomfortable it was. I finally asked him to stop. He looked around as if I couldn’t have been talking to him. He then apologized to the man (my spouse) I was sitting with for staring…at me. As if I wasn’t angry enough, I really went off then. The staff eventually asked him to leave. A manager apologized to me and a waitress said, “He came in the other night and was staring all creepy at me too. He even said some weird stuff.” The manager (a man) who just apologized to me, quickly turned around to ask the waitress, “Why didn’t you tell me?!” The waitress looked embarrassed and said she didn’t know. She said something at that moment, because she didn’t have to be the first one. Another waitress shared how the creepy-smile man had followed her to her car on another night.

When it comes to powerful people causing harm, coming forward about sexual harassment is so intimidating that many survivors never do. (I would also like to point out the difference between people telling their story in the media and filing claims privately.) When someone else takes the role of being the first, the pressure is slightly released. The flood gate begins to crack. There is a reason the battle cry for the anti-rape movement has been “You’re not alone” and “me too.” Experiencing sexual violence is so isolating it truly feels like no one understands and that you are the only one. When someone has a story that is similar, or the same person hurt both of you, the feeling of solidarity can be reviving.

What victim-blamers would call “a fad” or “jumping on the bandwagon,” we know is a very normal series of events in comfort and solidarity.

Back to TopicsHow the pandemic is affecting mental health – and what you can do about it

By Rachel Greis

CW: mentions of depression, anxiety, and self-harm

By now, we are all aware of the wide array of negative effects the COVID-19 pandemic has instilled within our communities and personal lives. The American Psychiatric Association conducted a survey wherein 37% of Americans reported that COVID-19 has had a serious impact on their mental health (American Psychiatric Association, 2020). The specific nature of COVID-19’s toll on mental health is still being determined as the pandemic rages on. However, researchers have compiled data from various studies on the effects of past infectious disease outbreaks and how they relate to a wide variety of mental health markers. Here is what we know:

- The existence of infectious disease outbreaks has been linked to increases in incidence of depression (Shultz et al., 2016) and anxiety (Jehn et al., 2011).

- A relationship has been established between mitigation strategies (e.g., social distancing, travel restrictions) and psychological distress (Maunder et al., 2003).

- The suspension of social activities has been shown to exacerbate these negative psychological effects (Cauchemez et al., 2009).

In the face of these challenges and countless others, it is essential to highlight the positive benefits of effective emotion regulation for overall psychological wellbeing. Psychologists define emotion regulation as “the process of initiating, maintaining, and modifying one’s emotional experience and expression” (Restubog et al., 2020). Managing and expressing our emotions can be really difficult, but understanding healthy and unhealthy ways to do so has been shown to enrich interpersonal relationships and even build resilience to stressful events (Tugade & Fredrickson, 2007).

Here are some examples of unhealthy ways to manage emotions (via Mental Health America):

- Withdrawing from others

- Engaging in self-harm behaviors (this can include substance use!)

- Lashing out at others

- Denying emotions altogether

Sometimes these unhealthy emotion regulation strategies may feel easiest, but it is important to strive for healthier ones such as:

- Processing emotions (e.g., drawing out or journaling about how you feel)

- Addressing your basic needs (e.g., hygiene, sleep/rest)

- Relaxing your body and mind (e.g., meditating, yoga, belly breathing)

- Engaging in hobbies that you enjoy!

- Asking for help

Practicing these healthy emotion regulation strategies is an ongoing, ever present act of self-awareness and growth. I encourage you reflect on your go-to strategies and implement new ones if you’re looking for a change!

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2020, March 25). New poll: COVID-19 impacting mental well-being: Americans feeling anxious, especially for loved ones; older adults are less anxious. https://www.psychiatry.org/newsroom/news-releases/new-poll-covid-19-impacting-mental-well-being-americans-feeling-anxious-especially-for-loved-ones-older-adults-are-less-anxious

Cauchemez, S., Ferguson, N.M., Wachtel, C., Tegnell, A., Saour, G., Duncan, B., & Nicoll, A. (2009). Closure of schools during an influenza pandemic. The Lancet Infectious Diseases, 9(8), 473–481. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1473-3099(09)70176-8.

Jehn, M., Kim, Y., Bradley, B., & Lant, T. (2011). Community knowledge, risk perception, and preparedness for the 2009 influenza A/H1N1 pandemic. Journal of Public Health Management and Practice, 17(5), 431–438. https://doi.org/10.1097/PHH.0b013e3182113921.

Maunder, R., Hunter, J., Vincent, L., Bennett, J., Peladeau, N., Leszcz, M., Sadavoy, J., Verhaeghe, L.M., Steinberg, R., & Mazzulli, T. (2003). The immediate psychological and occupational impact of the 2003 SARS outbreak in a teaching hospital. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 168(10), 1245–1251.

Mental Health America. (n.d.). Helpful vs. harmful: Ways to manage emotions. https://www.mhanational.org/helpful-vs-harmful-ways-manage-emotions

Restubog, S., Ocampo, A., & Wang, L. (2020). Taking control amidst the chaos: Emotion regulation during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Vocational Behavior, 119(103440). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2020.103440

Shultz, J.M., Cooper, J.L., Baingana, F., Oquendo M.A., Espinel, Z., Althouse, B.M., Marcelin, L.H., Towers, S., Espinola, M., Mazurik, L., Wainberg, M.L., Neria, Y., & Rechkemmer, A. (2016). The role of fear-related behaviors in the 2013–2016 West Africa Ebola virus disease outbreak. Current Psychiatry Reports, 18(11), 104. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11920-016-0741-y

Tugade, M.M., & Fredrickson, B.L. (2007). Regulation of positive emotions: Emotion regulation strategies that promote resilience. Journal of Happiness Studies, 8, 311-333. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-006-9015-4

Back to TopicsWhat happened to #MeToo in the 2020 election?

by Alayna Milby

Did you notice the missing headlines about sexual assault during the 2020 election? Thinking back to 2016 when Donald Trump was running against Hilary Clinton, it was difficult to scroll through social media without seeing something about Trump’s accusers. Harvey Weinstein’s decades long abuse was unraveling daily and Tarana Burke’s #metoo went mainstream as survivors continued to speak out against the long-hidden violence. The complacency our society has towards sexual harassment and assault was front and center. The conversation about survivors’ experiences were being had in spaces that seemingly banned these topics before. We called it a reckoning, a movement, a revolution. But here we are, now in 2021, and made it through a very contentious election cycle with little mention about accusations and abuse.

Survivors know people don’t want to talk about sexual violence. Survivors often don’t want to talk about it either. We know it makes people uncomfortable and we know the questions that follow. It is inconvenient to discuss trauma and sometimes inconvenient to listen. When #metoo dominated the news cycle and was used to call out politicians we don’t like, it was convenient. It was convenient to use survivors’ stories and trauma as a weapon. When #metoo was not only in headlines but on t-shirts and protest signs, we thought times were a’changing. Our culture would forever be changed. We knew people would continue to cause harm, we just thought they would be held accountable. We could come forward and talk about the abuse and something would change.

If our society’s standards are reflected in news headlines, media coverage, and social media trends, it is clear sexual violence will only be discussed when it is convenient. Not when both major party candidates have been accused of sexual assault. Not when sexual assault can’t be weaponized without pointing it at yourself or own party.

Looking back to 2016 and the years following, the coverage of sexual harassment was sometimes overwhelming. It seemed like you could never get away from it. Now, the absence is deafening.

Back to TopicsDepression

By Jill M.

Content Warning: description of depression symptoms

It slowly takes over a person’s life such as mine to the point where they forget how it all began. It is insidious, creeping up a little at a time. Little things change at first, leading to bigger changes. Then, as if out of the blue, that famous black cloud is overhead.

Depression is when everything feels too hard. When you feel so low that things you previously enjoyed no longer hold that same joy. You find it harder and harder to get out of bed in the morning. You drag yourself through each day. You find it difficult to go to bed at night.

How do you explain to someone that you want to live your life but also you don’t know how you can? How do you explain that this no longer feels like a choice, that it controls you not the other way around?

Depression is initially a reaction. A reaction to a life that you never imagined would be yours. A reaction to stress and a seeming inability to change your situation. It is an in-acceptance of how things are or were. It is lack of self-care and a giving too much of yourself to others. It is a deep anger at an injustice or unfairness in life. It is a lack of energy to take any more of what life has for you. It is a deep sadness and regret. It is all of this and much more. We are not always aware of why it happens because of how slowly and quietly it sneaks up on us.

I hope life gets easier for you. I hope you get that sense of control back. Lots of people like me have been through depression and come out the other side fighting everyday to win. Today begins OUR FIGHT, pick up your sword of strength and stand high, we’re not going anywhere until we win.

Healing Through History

by Maja Antonic, MA

Last month the United States marked the 100th Anniversary of women’s suffrage. In the past, this landmark victory remained largely unchallenged by the American public. However, as we find ourselves in times of national reflections on the collective past, the reception of this centennial commemoration appeared mixed. In theory, the 19th Amendment granted all women right to vote, but in practice racialized others were still excluded from a full citizenship since they still had to contend with poll taxes, literacy tests and economic disadvantages. History did not change but public’s perceptions informed by today’s standards transformed causing tepid responses to the legal victory attained a century ago. Understanding historical complexities becomes crucial in furthering our work as a sexual trauma recovery center. Deepening our own comprehension of historical and legal processes allows us to move the needle in the direction of acceptance and tolerance and permits us to better serve the survivors within our diverse community.

With the mentioned aim in mind, we must look at historical convergences that determine our cultural values and norms and in return shape our contemporary realities. The historical inquiry not only helps in answering the myriad of questions about sexual violence but more importantly, it enhances our comprehension about the correlation between the intersecting factors of gender, race, class, ability, national origin, sexual orientation etc. For our agency, historical exploration allows us to understand how we got here, why we do what we do while informing our community about the historical and legal complexities surrounding sexual violence. The questions such as: Where does the conceptualization of rape come from? How did the legal definitions of rape change over time? What is our regional/national history pertaining to sexual violence? How have the attitudes toward rape changed over time? What shaped our response to sexual violence within our justice system? How does gender/race/disability/sexual orientation/class correlate with sexual violence?

Many of these questions, if not all, can be answered by an existing vigorous research covering ever-changing meanings of sexual violence including rape. It is difficult to construe the fact that the definition of rape can alter because, after all, rape is rape. But legally and historically, prosecutions of sexual assault or rape depended on various intersecting social factors and continues to do so. For example, in the Antebellum South, poor white women carried the burden of proof if they accused their perpetrators of rape (Feimster, Southern Horrors). Aside from proving “force and lack of consent,” a sexually assaulted poor white woman had to “establish that she was a woman of previous ‘good fame’, provide evidence that she had disclosed the assault to a third party immediately, show signs of physical injury, and provide proof of her efforts to resist” (Feimster, Southern Horrors). This burden discouraged many women to come forward. For Black women, during the same period, the act of accusing, especially white men of rape, was a daunting, almost an impossible ordeal. Considered property by white, property owning population, Black women experienced acts of sexual violence by white males with impunity.

Understanding historical concepts is one thing, but accepting troublesome past is another. Informing and educating alone will not help us in forcing more empathy from others. But it is a starting point required to discern why our society still has a difficult time believing the survivors based on an accuser’s identity. Or why do we accept the current rates of perpetration among our youth. To search for explanations, we need to examine the attitudes held by those who came before us. During the colonial era, Native women were perceived as sexually available objects by Western Europeans migrants which ran in contrast with their local customs (Freedman, Redefining Rape). While rape occurred within the native societies, it was reserved for a capture of women from the opposing camp who would later become wives or concubines (Freedman, Redefining Rape). New Western European arrivals would instead deem native women as prostitutes available for their sexual conquests (Freedman, Redefining Rape). The colonial legacy including the introduction of the Western European social order disrupted the native people’s own social order and way of life. Or as Sarah Deer posits: “Sexual assault mimics the worst traits of colonization in its attack on the body, invasion of physical boundaries, and disregard for humanity.” (Deer, 150). Decolonizing rape, therefore, becomes a crucial component of redefining our laws to address the effects caused by colonization including sexual violence for racialized/gendered/disabled others.

Western European colonizers brought over their own legal codes and social attitudes about rape and imposed it on native societies and non-white individuals. Aside from this imposition, British Law Code treated rape as a serious offense according to a historian Estelle Freedman. However, the prosecution rates did not reflect the seriousness of the law and instead class and race determined who can accuse someone of rape. While in the new Republic, class played an important role in determining someone’s reputation and at times complicity with the crime as mentioned above in the case of poor white women, more increasingly race started to determine an individual’s worth. Particularly in the South, two racial beliefs about rape emerged during the Antebellum era: (1) Back women cannot be raped and (2) Black men threatened white female virtue (Freedman, Redefining Rape). These two ideas continued to dominate public perceptions about Black women and Black men well into the 20th century. Black women were deemed as sexually insatiable while an image of a Black male rapist installed unsubstantiated stereotypes into the Southern consciousness. Today, we still contend with these misconceptions as Black women and Black trans individuals are less likely to report rape than their white counterparts.

Acknowledging difficult components of the American collective past can help us in overcoming centuries held misconceptions and damaging stereotypes. As a nation and a region, we have a responsibility to include troubling and painful realities of the past in our everyday rhetoric and our children’s textbooks with the intent to create more compassionate generations. For the survivors of sexual assault, the recognition of their respective social challenges can make a healing process more effective. After all, healing takes some time but with informed and caring support systems in place, we can serve the survivors more successfully while fulfilling our commitment to the creation of safer, more empathetic communities.

Bibliography

Deer, Sarah. “Decolonizing Rape: A Native Feminist Synthesis of Safety and Sovereignty.” Wicazo Sa Review (FALL 2009) Vol. 24, No. 2. Native Feminism (149-167).

Feimster, Crystal N. Southern Horrors: Women and the Politics of Rape and Lynching. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press., 2009).

Freedman, Estelle. Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation. (Cambridge: Harvard University Press., 2013).

Back to TopicsI Just Want Him to Get It.

By Alayna Milby

“You knocked down both our towers, I collapsed at the same time you did. If you think I was spared, came out unscathed, that today I ride off into sunset, while you suffer the greatest blow, you are mistaken. Nobody wins. We have all been devastated, we have all been trying to find some meaning in all of this suffering. Your damage was concrete; stripped of titles, degrees, enrollment. My damage was internal, unseen, I carry it with me. You took away my worth, my privacy, my energy, my time, my safety, my intimacy, my confidence, my own voice, until today.”

Know My Name: a Memoir by Chanel Miller

My mom texted me, I just finished Know My Name by Chanel Miller and it is so good! You should too. I listened to it on Audible.

It is so good? A survivor sharing her traumatic experience of a highly publicized sexual assault is so good? This wasn’t the first time my mom suggested I read articles or books or watch videos or films about sexual assault survivors. When I was hired at Hope Harbor in 2015, I thought reading everything that covered sexual assault was like research preparing me for work with survivors. In 2016 for Sexual Assault Prevention Month, Western Kentucky University Counseling Department acquired the rights to show The Hunting Ground, a film about campus sexual assault. I found, along with many others in the movement, this to be groundbreaking! A film getting a lot of media attention showing the truth of what we know happens every day! I now know this film was released by the Weinstein Company, but that’s another blog post to dissect. I asked my coworker if she was going to the event. Uh heck no. Why? I asked. I live this every day. I know what happens, the victim blaming, universities covering it up by doing nothing. Why would I want to watch that? I said something that implied I understood and walked away. But I didn’t understand, at least not at that point when I had been working at Hope Harbor for six months. I brushed it off as being pompous. I didn’t go to the showing either though, but because I had already watched the film on Netflix. I thought it was great! So informative and powerful, plus Lady Gaga did that song at the end and I love Lady Gaga.

In 2018, I attended a conference where the closing session was a showing of The Hunting Ground. I decided to stay for it, even though I had seen it, because I had presented at the conference and I didn’t want to be rude by leaving early. I sat at a table with women I had met earlier that day, all advocates within the movement. This time I watched the film through the eyes and ears of a sexual assault advocate that had heard countless stories, been on dozens of hospital calls with survivors, and had daily conversations about the struggles those we advocate for face: victim blaming, cases going nowhere, abusers claiming it was consensual. As one survivor in the film explained the way the police treated her when reporting her assault, the woman to my left in a military uniform began shaking her head, holding back tears. I now saw this film as triggering. Dramatic details and shock value images to disrupt the audience as if none of us in the room were survivors ourselves. As if this is the first time we had heard these claims of victim blaming and mistreatment. The first time we had heard abusers get to go on and become first draft pick for the NFL. The woman to my left, now crying, gathered her things in a hurry and said to me I can’t watch this. Why are they showing this HERE?! I agreed and she walked out. I now understood why my coworker in 2016 said no to this film. This film wasn’t made for survivors and advocates. I assumed all documentaries would be like this and I said I wouldn’t torture myself any longer.

This went on for years; I would avoid all mainstream media covering sexual violence. But this year is different, because of course it is. I am working from home and finding tasks that don’t involve staring into a computer for 8 hours a day. I took up my mom’s suggestion, downloaded Audible, and used my first free book credit on Know My Name. Here are my takeaways:

No one can deny Chanel Miller is an artist and her viral victim impact statement made clear her power with words. Her memoir is no different, especially listening to her words in her voice. Her writing made her story approachable, digestible, and in my opinion, safe for survivors.

Even if you haven’t read her book, you probably know her story. People across the country outraged by a California judge’s sentencing of six months in county jail following three guilty verdicts by a jury. Two witnesses to the assault of an unconscious woman. Chanel said she didn’t necessarily choose to press charges, but that she was given no other options. She was interviewed by law enforcement hours after the assault she doesn’t remember, learned details of what happened to her in the news, and then approached about pressing charges. Either yes or no. Know My Name is Chanel’s memoir and gives a look inside her upbringing, living in a town with absurdly high suicide rates, surviving a mass shooting at the University of California Santa Barbara, and what we expected her to discuss: the assault at Stanford University. I hope those reading Know My Name, and this blog post, recognize the disruption she and her family experienced due to the criminal legal case. Chanel notes the person who hurt her was punished, where most survivors never get that result. It is estimated out of 1000 sexual assaults, only five perpetrators will see a day in jail. That statistic alone makes Chanel’s story unique. But in her book, Chanel does not describe glory or safety or feeling happy about this result. While there was a guilty verdict, the sentencing was 6 months with him serving only 3 months. Her justice, her success, his punishment was measured by months in jail.

When interviewed by the parole officer, Chanel said, I just want him to get it. At Hope Harbor, staff and volunteers have been discussing alternatives to reporting to law enforcement like restorative and transformative justice. We can clearly see the criminal justice system does not serve survivors of sexual assault and we need more options if we truly want to end violence in our communities and provide survivors with support. While Chanel doesn’t mention these forms of justice in Know My Name, I can only imagine what option she would have chosen if she were given any. If there was a way for someone who has caused harm to get it, what would that look like for us? What would Chanel, and so many others, have been spared if they had another option outside the criminal justice system?

Chanel says she lived two lives during those years. One as Chanel and the other as Emily Doe, keeping her lives separate. One traveled across the country to take classes on print making, while the other scheduled around hearings, taking phone calls from the district attorney, and writing a victim impact statement. Hearings would be postponed and plans would be put on hold. Her life revolved around these phone calls and waiting to hear back about decisions being made without her. Most people would not be able to do what she did during these years of the case going through trial. Chanel couldn’t work, her family and boyfriend supporting her after her savings ran out. She briefly mentions this privilege and acknowledges not everyone would have the same opportunity, but it was overwhelmingly obvious to me so few would ever have a similar story. She has a support system many would only dream of: both parents, sister, grandparents, friends since childhood, college friends, boyfriend. If any of her close family or friends ever questioned her experience, ever made victim blaming statements, Chanel doesn’t talk about it in her memoir. If Chanel ever wondered how she would pay bills after quitting her job due to distress, she doesn’t talk about it in her memoir. She does mention how expensive it is to be sexually assaulted, but if she worried about where that money would come from, she doesn’t mention it in her memoir.

Chanel’s story should be told and listened to. I truly believe there is a lot to gain from hearing her story, reading her words, knowing her name. I also think there is a lot more to gain when we recognize the limitations and exuberant costs of the criminal justice system, how survivors and perpetrators of different races and class are treated in our country, and how few of them will we ever know their names.

Back to Topics

Can You Hear Them Now? Good.

By Sarah Hamilton

“One of those days where you listen long enough to the sound of the sea birds and the water and the wind and you give up on words for a while because none of them are big enough”

Brian Andreas, Listen Long

I am starting year six of higher education and my second year of graduate school for mental health this fall, and I still have not had that class that teaches you how to read minds. So how can I possibly help anyone? It’s impossible to know what someone needs in a moment without knowing what they’re thinking, but how on earth do we know what they are thinking?

Maybe this thought sounds familiar to you. Someone you love is going through a heavy time and you have no idea how to lift the world from their shoulders. It is only natural to want to help or to lend a hand in some way and it is so easy to get wrapped up in the self doubt of, “who am I to make a difference in this moment?” How many times do we blame ourselves for not having the right tools in our tool boxes to fix a situation for someone, or have the knowledge to know how to use the tools even if we had them? What if I told you that you already have the most useful tool there is and this blog is just a means of helping you understand this preexisting tool? It doesn’t require a degree or thousands of dollars in specialized training to be able to help someone you love, it doesn’t even require a room filled with words and conversation. Simply, it is allowing them the experience of being listened to.

First things first, if you’ve been paying attention, the previous paragraph is riddled with responsibility-implying language. Lets get it clear you cannot take on the responsibility of “fixing” a moment for someone and, in general, you cannot “fix” someone; it is impractical to expect that of yourself and will likely only make you feel worse or like you have failed them when you cannot fix it. Let go of that blame, guilt, responsibility, or whatever it is you feel when you cannot lift the world from someone’s shoulders. Next, I want you to pat yourself on the back for being here, reading this blog. Give yourself some grace for what you’re doing for that person you love right now: reading and educating yourself on how you can show up for someone. Now that we have managed expectations, we can begin to listen.

It is easy to forget how impactful truly listening to someone can be, especially when the world around us constantly reminds us it is a weakness or missed opportunity to not make ourselves heard. In her book You’re not Listening: What You’re Missing and Why it Matters, Kate Murphy sums it up best, “In a culture infused with existential angst and aggressive personal marketing, to be silent is to fall behind. To listen is to miss an opportunity to advance your brand and make your mark.” Everything about American culture encourages us to be heard, but what happens when words aren’t big enough anymore?

Everyone has something to say and no one has the patience to listen. We all do it, even me. When my friends tell me stories and they pause for a moment looking for the right word, I am quick to jump in with the word I think they’re looking for. While well-meaning when I do this, I have started to wonder: what am I missing when I do not listen? What important piece of their story am I missing out on and taking away from them when I offer my two cents to the conversation prematurely? What would they have said if I didn’t interject? These are the moments we must be mindful of to truly listen and be present.

Reflect on those individuals who you have interacted with today, yesterday, the past week, or any notable time. Did you interrupt them? Respond in a manner implying you only caught the jist of what they were telling you? Did you let distractions get the better of you? Or maybe you were done with the conversation or uncomfortable and displayed nonverbals that communicated your discomfort? Worse yet, did you intermittently pick up your phone while they were speaking? Each of these things is something everyone is guilty of at some point and even when we have the best intent in doing them, we take away someone’s experience of feeling fully listened to. To change these poor listening habits we first have to acknowledge them and build awareness of their presence in our conversation.

When you find yourself wanting to interject, consider what you might miss when you cut their story short. Think deeply about what someone is telling you and respond not only to their spoken words, but the feeling and emotion behind what they say. Pay attention to your non-verbals and what message they are sending someone and pay attention to someone else’s nonverbals: actions speak louder than words. Cultivate awareness around when you pick up your phone in a conversation and put it right back down when you catch yourself. It is a process of being patient with yourself to build these listening skills, but you can learn! When someone says something you don’t follow, ask for clarity. Likely, instead of being frustrated, they will be grateful someone is listening.

Listening is critical in helping. Next time someone you love is having a rough day, ask what they need and listen. That, my friends, answers our question of “how could we possibly know what someone is thinking?” Would you have ever assumed the answer would be so simple as to ask? Until that mind reading class enters the curriculum, this is the best answer I can give you for knowing someone else’s thoughts. We ask and we listen deeply without an agenda and assumption of the way things should go from there. Words aren’t big enough to take the world off someone’s shoulders, but listening and allowing someone to feel heard can do wonders for relieving some of the weight. Think about it; how do you feel when finally given the opportunity to spill what is on your mind? There is a power in that verbal release.

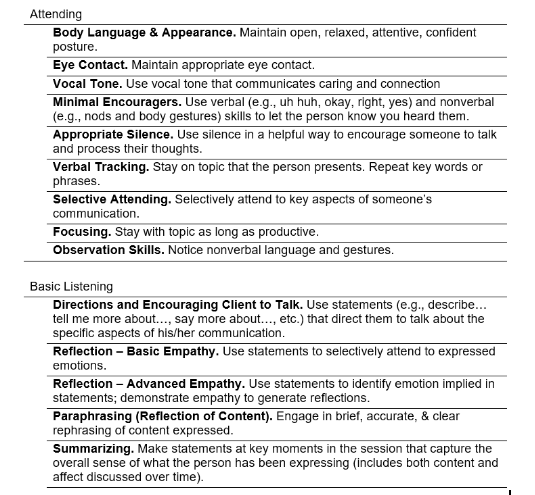

If the art of learning to listen has piqued your curiosity, I invite you to check out the book I mentioned in this post. You’re not Listening: What You’re Missing and Why it Matters by Kate Murphy nicely elaborates the critical need of listening and provides an in-depth look on why listening matters. For quick reference, I have included a list of basic listening skills below. This is directly from a counseling skills scale checklist used in my graduate program for counselors-in-training. Ever wonder what skills your counselor uses in sessions? Not only will you now know how counseling works, you can research these skills and use them everyday!

Western Kentucky University, Department of Counseling and Student Affairs: Counseling Skills Scale

References

Murphy, K. (2020). You’re not listening: What you’re missing and why it matters. New York: Celadon Books.

Back to TopicsReleasing the Past: Unburdening the Present

by Sarah Hamilton

“If the problem with PTSD is dissociation, the goal of treatment would be association: integrating the cut-off elements of the trauma into the ongoing narrative of life, so that the brain can recognize ‘that was then, and this is now.’”

Bessel Van Der Kolk, The Body Keeps the Score

Life is ever changing, each day is different from the previous and non-assuming of what the next day may bring. This is the ongoing narrative of life, each day an opportunity for a new story. The ability to live in the present is essential for our optimal day-to-day functioning. Oftentimes, the present gets interrupted by dwelling thoughts of yesterday or hopes for future days to come. Even moments in the day are overlooked for thoughts of that all-important 2:00 meeting you’re facilitating.

Similarly, for those who have experienced trauma, the present is overlooked and the past takes control of our day. The core symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) are intrusive experiences, avoidance, negative thoughts or moods, and alterations in reactivity (American Psychiatric Association, 2013). These symptoms are inherently past-oriented and prevent us from processing and being in the moment.

Intrusive experiences are constant reminders of past events, making it impossible sometimes to focus on the moment we’re in. Avoidance of people or places indicates an inability to process events that happened with a person or at a specific place, hindering our ability to live in the moment and go where we please in our day. Negative thoughts and/or moods leave us unable to connect with others and diminish our interest in activities we once enjoyed, significantly impacting how we live in the present. Finally, noticing marked changes in how we react to our environment such as someone touching your shoulder suddenly sending you into a fit of rage, are reactions to past memories we have not yet processed. Not only do we have these unprocessed past memories impeding our capacity to live in the present, but often with them come a number of physical complaints like heaviness in our chest, constantly sore shoulders from carrying tension all day, or maybe it’s a never ending headache.

After trauma the past becomes the burden of the present and not only do our brains store those memories, but our bodies carry that heaviness of our brains holding on to the past.

Proper healing from trauma would encapsulate each relevant symptom, as well as addressing those physical symptoms we feel in our body. Traditional therapies (e.g. processing therapies, insight-oriented therapies, and exposure therapies) are undoubtedly effective; however, each gives way to unique concerns in practice. Processing therapies can be difficult for those having experienced multiple traumas from a young age into adulthood as it becomes complex to process each individual trauma. Insight-oriented therapies pose difficulty for those who have experienced long-term trauma as it is understood that the longer trauma has occurred, the more challenging it is to verbally express those experiences. Finally, exposure therapies are placing individuals with triggering aspects of their trauma; while this is an effective therapy, dropout and incompletion rates are high due to the difficulty of trauma exposure. If you’ve noticed too, each of these therapies are focusing on the past, not the present. Similarly, none of them have addressed the physical storage of trauma in the body (West et al., 2017).

How is it then that we begin to re-orient ourselves to the present while also addressing the physical storage of trauma in the body? Looking beyond or in supplement to these traditional therapies at healing in alternative therapeutic practices such as yoga, we can find an all-encompassing means of coming back to the present and releasing the weight that comes with carrying it.

Trauma Sensitive Yoga (TSY) is a practice that works to cultivate healing from trauma exposure through gentle teaching and a safe environment to bring forward compassionate, non-judgemental awareness of what is happening in our bodies in the moment. From this awareness comes a recognition of choice and control over one’s body and in turn the development of ability to take effective action based on these signals from our body. During a TSY class one might notice instructors using invitational language (“Next I invite you to do…”) as opposed to commanding language (“next we will be doing…”) to facilitate a safe environment where participants have a choice in what they do. Any language used is present centered and directed at in-class experiences (“Notice your posture in how you are sitting in class right now” v.s. “Think about your posture at the beginning of the day vs. the end of the day”). Finally, there is no group processing of traumatic experiences during TSY, there is only the now and what’s happening in the present (West et al., 2017).

One research study that examined the experiences of participants in a TSY class identified five overarching themes reported by participants as grace and compassion, relation, acceptance, centeredness, and empowerment. Grace and compassion were described as an increased physical awareness of one’s body as well as the integration of doing what is right for their body leading to increased gentleness with their bodies and patience with the process of change. Relation was identified as participants being able to reflect inward on their bodies and identify physical sensations and emotions that arose for them; strengthened interpersonal relationships were also identified. Acceptance was found among participants as heightened ability to accept themselves for who and where they are in life as well as finding peace in what has been and currently is in life. Centeredness was described as having a quieter, less ruminative mind/thoughts, ability to see multiple perspectives, and overall feel more positive. Finally, empowerment was described as a greater sense of control over one’s life and confidence to take the control (West et al., 2017).

TSY is a present-centered approach that allows healing in a safe, controllable environment. Yoga can be done in addition to or in supplement to traditional therapy approaches as well. After trauma, it is important we recognize what our body is trying to tell us. You have the power to be in control and the power to heal and help yourself. You never lost it. We are the masters of our body and we know what it needs, we just have to remember to listen to it. TSY only heightens and guides those preexisting capabilities to listen to ourselves.

Hope Harbor Yoga Videos can be found on our YouTube Channel

References

American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (5th ed.). https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.books.9780890425596.

West, J., Liang, B., & Spinazzola, J. (2017). Trauma sensitive yoga as a complementary treatment for posttraumatic stress disorder: A qualitative descriptive analysis. International Journal of Stress Management, 24(2), 173–195. https://doi-org.libsrv.wku.edu/10.1037/str0000040

Van der Kolk, B. A. (2014). The body keeps the score: Brain, mind, and body in the healing of trauma. New York: Viking.

Back to TopicsIntro- Thanks for Asking: A Blog by Hope Harbor

Beginning in 2020, Hope Harbor recognized the need for information about trauma and responding to trauma for the survivor community we serve. All experiences are different, but it can be comforting to know we are not alone in this struggle. Sexual violence can be isolating and information covering clinical research can be limited to certain groups. We are using our blog, Thanks for Asking, as a space for shared knowledge and resources to reach a wider audience.